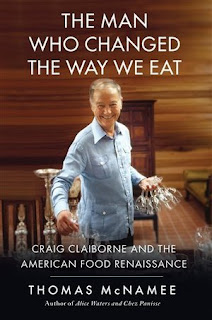

New York, Free Press, 2012

291 pages Biography

Craig Claiborne was a food writer and

critic for the New York Times from the mid 1950s until the mid 1980s. Although

relatively unknown today, he changed the way Americans thought about food and restaurant

fare and helped create a new generation of chefs who developed the epicurean climate

that exists today in magazine, television, and books as well as on our dinner tables.

Thomas McNamee tells Claiborne's story in the biography, The Man Who

Changed the Way We Eat. The subtitle: Craig Claiborne and the American Food

Renaissance just about tells it all. This is a straightforward biography--chronological,

and tightly scripted. It speaks of Claiborne’s childhood in Mississippi, the

son of a woman who ran a boarding house where good southern cooking was the

daily norm. He was educated at the University of Missouri and then at a

culinary school in Switzerland. He virtually willed himself into the job as

food critic of the New York Times. One of his first articles was a condemnation

of the culinary arts of the 1950s. It was on the front page of the New York

Times in 1959. The article caused a sensation and made his career.

Claiborne was a “king maker”; his say could make or break a

restaurant or a chef. This was before the days of “celebrity” chefs, the Food

Channel, or even Public Television’s cooking shows. Cook books, including the

Joy of Cooking were utilitarian. Claiborne changed all that. His endorsement of

Julia Child’s cookbook made her famous. He felt quite strongly that chefs

needed to be grounded in classic cooking before they could take off on their

own ideas “to be innovative to the limits of their imaginations.” He loved all

the cooking of the world and loved serving and eating cuisines of various

cultures in one meal. He was a great cook in his own right and a wonderful

host. He also enjoyed taking friends and co-workers out for meals, trying out

new restaurants, or having favorite dishes at favorite restaurants. Much of

what we have in our American cupboards and refrigerators today came about

because Claiborne wrote about it—garlic, cilantro, fresh ginger, goat cheese,

basil, pine nuts, arugula, balsamic vinegar, macadamia nuts. He even endorsed

the salad spinner. Certainly these were things unknown to me as I began to cook

in the 1960s, and certainly they were unknown to most Americans.

Claiborne was a “king maker”; his say could make or break a

restaurant or a chef. This was before the days of “celebrity” chefs, the Food

Channel, or even Public Television’s cooking shows. Cook books, including the

Joy of Cooking were utilitarian. Claiborne changed all that. His endorsement of

Julia Child’s cookbook made her famous. He felt quite strongly that chefs

needed to be grounded in classic cooking before they could take off on their

own ideas “to be innovative to the limits of their imaginations.” He loved all

the cooking of the world and loved serving and eating cuisines of various

cultures in one meal. He was a great cook in his own right and a wonderful

host. He also enjoyed taking friends and co-workers out for meals, trying out

new restaurants, or having favorite dishes at favorite restaurants. Much of

what we have in our American cupboards and refrigerators today came about

because Claiborne wrote about it—garlic, cilantro, fresh ginger, goat cheese,

basil, pine nuts, arugula, balsamic vinegar, macadamia nuts. He even endorsed

the salad spinner. Certainly these were things unknown to me as I began to cook

in the 1960s, and certainly they were unknown to most Americans.

When his career at the New York Times ended, much of who

Craig Claiborne was ended as well. His heart began to fail; he descended into

alcoholism and self-pity. He died in 2000 at the age of 80. McNamee

says of his life: “He had lived as he

had wished to live, had led his fellow Americans into vast new realms of

enjoyment, and had had a lot of fun along the way, his way.”

Craig Claiborne was a complex person, and McNamee touches on

many of his complexities, but perhaps in too straightforward a way. Much of the

speculation about Claiborne’s propensities and peculiarities remain just that,

with very little exploration of what really made the man tick. The review of The Man Who Changed The Way We Eat in

the Los Angeles Times notes that Claiborne was: “Almost unfailingly helpful to

others but utterly ambitious. Prim and proper but given to raging fits when

drunk. A man who treasured his friendships yet ended up alienating almost

everyone close to him. Someone who delighted in socializing with the chefs he

covered but basically invented the ethical rules for restaurant critics.” The

same reviewer suggests that McNamee didn’t attempt to understand any of these

characteristics of the man. Much of the book depends on the reminiscences of Diane

Franey, the daughter of Claiborne’s business partner, Pierre Franey, a chef and

cookbook author. Some of what is missing in the book are the recollections of

people at the New York Times. That would have been helpful.

My mother was a good cook, although not a brilliant one. She

kept lots of recipes and tried out ones that she found in the newspaper and in

magazines. She prided herself on serving well-prepared meals for guests. We

never had TV dinners, and only occasionally had Banquet Chicken Pot Pies. I

will never forget going to visit some friends for a Sunday dinner. The wife

served frozen pot pies over mashed potatoes and my mother was a bit miffed

about it. She commented on the way home that she would never do something like

that. But, in the 1950s, a frozen chicken pot pie was a new “delicacy,” and I

think that the wife thought she was serving us something special. What would

Craig Claiborne have to say about that!

You might want to check out my posting about Taste What You’re Missing by Barb Stuckey. It discusses the scientific aspects of good food.

A review of The Man who Changed The Way We Eat in The Los

Angeles Times: http://www.latimes.com/entertainment/news/la-ca-thomas-mcnamee-20120520,0,4240373.story

A blog posting by Thomas McNamee in the Huffington Post: http://www.huffingtonpost.com/thomas-mcnamee/famous-food-critic_b_1497904.html