by Peter Hessler

New York, Harper Collins

425 pages Non-Fiction

In my job as an academic editor, I come face-to-face with China nearly every week. My latest project has been to edit the English translation of the Beijing Normal University website. My contact at the university is named Nicole, and the other company representatives are Derek, Harrison, and Alex. All of these people are Chinese and live in Beijing and Shanghai.(Why the English names, I have no idea—I guess because they are dealing with Americans.) A few weeks ago, I edited a journal article about Internet addiction among Chinese students. Even in my limited experience, I can see that China is changing rapidly. I am fascinated by the changes.

Peter Hessler lived in China for about ten years, worked as bureau chief for the New Yorker magazine in Beijing, and has written three books about his experiences there. Country Driving is the third; doubtless it will not be the final book. The other books in the series are River Town and Oracle Bones.

Country Driving: A Journey through China from Farm to Factory is divided into three parts, all about Hessler’s experiences in the countryside of China. In the first section, Hessler follows the Great Wall for several thousand miles, camping in the wilderness, having his hair washed in small villages, and picking up hitchhikers along every route. The hitchhikers are usually young people from the industrial centers of the country traveling home to visit parents in the small rural villages.

This is a country that is just learning how to drive, and Hessler delights in telling the readers about the challenges of driving among countrymen, most of whom have had a driver’s license for less than three years. Such experiences include left turns from the right lane and passing on the right-hand sidewalk. He has encounters with local police who kick him out of their villages for being a spy. Because he speaks fluent Chinese, he can ask the locals the right questions and they help him find the interesting local people who can explain local life to him. He reminds the reader that China is in the midst of the largest migration in human history and most small rural villages are devoid of young people or children. He also throws in history and folklore about the Great Wall.

The second section of the books is about a small village outside Beijing where Hessler finds a small house to use as a weekend retreat. He spends several years there and becomes extremely good friends with a local innkeeper, his wife and small son. They are the only young couple in the village and their son is the only child. This is the most significant portion of the book, because it exposes the reader to the immense changes happening through the experiences of one family. We learn about to the health care system, the education system, free enterprise, the local Communist party and changes in eating habits.

The third section talks about one small region of China and the changes that come when industry moves in. Along the way, Hessler reminds us constantly that things are changing so rapidly that people can’t adapt; there is a hollowness that comes when one’s roots are torn from their grounding. He says, “The longer I lived in China, the more I worried about how people responded to rapid change. This wasn’t an issue of modernization…But there are costs when this process happened so fast…from what I saw, the nation’s great turmoil was more personal and internal. Many people were searching: they longed for some kind of religious or philosophical truth, and they wanted a meaningful connection with others. They had trouble applying past experiences to current challenges. Parents and children occupied different worlds and marriages were complicated-rarely did I know a Chinese couple who seemed happy together. It was all but impossible for people to keep their bearings in a country that changed so fast.”

We know these things are happening in China because we are exposed to the results of the change every day. Hessler documents them with uncanny accuracy and with good humor. This is not a travelogue in the traditional sense, but the reader certainly wishes to have been along for the drive with such a natural tour guide.

This book was named one of the New York Times best books of 2010.

A review in the New York Times.

http://www.nytimes.com/2010/02/28/books/review/Becker-t.html

A blog review by a Beijing resident:

http://www.blogger.com/goog_847942970

A speech before the Asia Society:

http://asiasociety.org/video/countries-history/chinas-open-road-peter-hessler-complete

Welcome to my blog. I am Miriam Downey, the Cyberlibrarian. I am a retired librarian and a lifelong reader. I read and review books in four major genres: fiction, non-fiction, memoir and spiritual. My goal is to relate what I read to my life experience. I read books culled from reviews in The New York Times, The New York Review of Books, Bookmarks, and The New Yorker. I also accept books from authors and publicists. I am having a great time. Hope you will join me on the journey.

Search

Sunday, January 30, 2011

Friday, January 21, 2011

The Soul of Christianity: Restoring the Great Tradition

By Huston Smith

Harper San Francisco, 2005

176 p. Spiritual

Huston Smith is an historian of religion that I first met when I read the Harvard Psychedelic Club (reviewed in November, 2010). He was in his late 80s when he wrote The Soul of Christianity and has just this year published his memoirs, “Tales of Wonder: Adventures Chasing the Divine.” Time magazine has called him a "spiritual surfer." "Christianity has always been my religious meal," Smith has said. "But I'm a great believer in vitamin supplements." You may know him from a 5-part PBS series Bill Moyers produced in 1996 called, The Wisdom of Faith with Huston Smith.

This book, The Soul of Christianity, is his apology—his defense of Christianity. Although in his career he has written and taught world religions, he is a Christian to his very core. He says: “One of life’s quiet excitements is to stand somewhat to one side and watch yourself softly become the author of something beautiful. I experienced that excitement often in writing this book.”

Smith divides the book into three parts: The Christian Worldview, The Christian Story, and The Three Main Branches of Christianity Today. The first section, The Christian Worldview, is the most philosophical and the most difficult to digest, although I felt that his defense of a worldview that includes God was very articulate and understandable. He numbers each of his points, and then elucidates them, so it is easy to go back to think through a particular point in a clearer fashion.

Here are some points that I particularly liked:

1) Science’s technical language is mathematics; religion’s technical language is symbolism.

2) “God’s pervasiveness needs to be experienced and not just affirmed.”

3) “We miss the truth if we content ourselves with fragments.”

4) In trying to prove the existence of God, we must “distinguish the absence of evidence from the evidence of absence.”

5) “A bridge must touch both banks, and Christ was the bridge that joined humanity to God.”

6) “Every time we abuse the poor, every time we pollute our God-given planet, indeed, every time we act selfishly, God dies naked on the cross of our ego.”

Of course several reviewers take exception to Smith’s theology and his “worldview” of Christianity, but I found his explanation of the Christian story to be the orthodox, century’s old story, very consistently told, and traditional in tone. I also thought that his brief explanations of the three major Christian divisions—Roman Catholicism, Eastern Orthodoxy, and Protestantism to be very concise. A novice Christian would learn a lot about the Christian religion from both sections of the book.

The impression I retained from reading this book is that Huston Smith was writing from his heart as well as from a career of teaching religion. I envisioned him, an old man, sitting at his desk, pondering the pearls of wisdom he could relate to a secular world. He mentions that this book might be his last book on religion; what could he say that would have meaning? What he is saying is that even after a lifetime of studying the religions of the world, he still chooses Christianity for himself and believes that Christianity is where his soul lies. That I was able to agree with him so completely probably means that this is where my soul lies as well.

Reviews of this book are all over the place depending on how fundamentalist or liberal the reviewer is. Several reviewers noted that although they took exception to some of Smith’s theology, they believe that Smith gave a concise, readable overview of Christianity.

A review that was in full accord with Smith’s theology: http://www.explorefaith.org/books/soulofchristian.html

A review that liked the book but objected to some of the theology:

http://www.journeywithjesus.net/BookNotes/Huston_Smith_The_Soul_Of_Christianity.shtml

A review that hated the book:

http://www.equip.org/articles/the-soul-of-christianity-restoring-the-christ-tradition

An interview about this book on beliefnet.com:

http://www.beliefnet.com/Faiths/Christianity/2005/11/God-Speaks-To-Each-Person-In-Their-Own-Language.aspx

Huston Smith’s website:

http://www.hustonsmith.net/

Harper San Francisco, 2005

176 p. Spiritual

Huston Smith is an historian of religion that I first met when I read the Harvard Psychedelic Club (reviewed in November, 2010). He was in his late 80s when he wrote The Soul of Christianity and has just this year published his memoirs, “Tales of Wonder: Adventures Chasing the Divine.” Time magazine has called him a "spiritual surfer." "Christianity has always been my religious meal," Smith has said. "But I'm a great believer in vitamin supplements." You may know him from a 5-part PBS series Bill Moyers produced in 1996 called, The Wisdom of Faith with Huston Smith.

This book, The Soul of Christianity, is his apology—his defense of Christianity. Although in his career he has written and taught world religions, he is a Christian to his very core. He says: “One of life’s quiet excitements is to stand somewhat to one side and watch yourself softly become the author of something beautiful. I experienced that excitement often in writing this book.”

Smith divides the book into three parts: The Christian Worldview, The Christian Story, and The Three Main Branches of Christianity Today. The first section, The Christian Worldview, is the most philosophical and the most difficult to digest, although I felt that his defense of a worldview that includes God was very articulate and understandable. He numbers each of his points, and then elucidates them, so it is easy to go back to think through a particular point in a clearer fashion.

Here are some points that I particularly liked:

1) Science’s technical language is mathematics; religion’s technical language is symbolism.

2) “God’s pervasiveness needs to be experienced and not just affirmed.”

3) “We miss the truth if we content ourselves with fragments.”

4) In trying to prove the existence of God, we must “distinguish the absence of evidence from the evidence of absence.”

5) “A bridge must touch both banks, and Christ was the bridge that joined humanity to God.”

6) “Every time we abuse the poor, every time we pollute our God-given planet, indeed, every time we act selfishly, God dies naked on the cross of our ego.”

Of course several reviewers take exception to Smith’s theology and his “worldview” of Christianity, but I found his explanation of the Christian story to be the orthodox, century’s old story, very consistently told, and traditional in tone. I also thought that his brief explanations of the three major Christian divisions—Roman Catholicism, Eastern Orthodoxy, and Protestantism to be very concise. A novice Christian would learn a lot about the Christian religion from both sections of the book.

The impression I retained from reading this book is that Huston Smith was writing from his heart as well as from a career of teaching religion. I envisioned him, an old man, sitting at his desk, pondering the pearls of wisdom he could relate to a secular world. He mentions that this book might be his last book on religion; what could he say that would have meaning? What he is saying is that even after a lifetime of studying the religions of the world, he still chooses Christianity for himself and believes that Christianity is where his soul lies. That I was able to agree with him so completely probably means that this is where my soul lies as well.

Reviews of this book are all over the place depending on how fundamentalist or liberal the reviewer is. Several reviewers noted that although they took exception to some of Smith’s theology, they believe that Smith gave a concise, readable overview of Christianity.

A review that was in full accord with Smith’s theology: http://www.explorefaith.org/books/soulofchristian.html

A review that liked the book but objected to some of the theology:

http://www.journeywithjesus.net/BookNotes/Huston_Smith_The_Soul_Of_Christianity.shtml

A review that hated the book:

http://www.equip.org/articles/the-soul-of-christianity-restoring-the-christ-tradition

An interview about this book on beliefnet.com:

http://www.beliefnet.com/Faiths/Christianity/2005/11/God-Speaks-To-Each-Person-In-Their-Own-Language.aspx

Huston Smith’s website:

http://www.hustonsmith.net/

Labels:

Christianity,

Huston Smith,

Spiritual Growth

Friday, January 14, 2011

Just Kids

By Patti Smith

New York, Harper Collins, 2010

288 pages Memoir

Up there, Down there

from Dream of Life by Patti Smith

Up there, there’s a ball of fire

Some call it the spirit, some call it the sun.

It’s energies are not for hire.

It serves man, it serves everyone.

I am listening to Patti Smith music today, trying to connect with an era I missed completely, because I was studying theology--of all things--getting married and having babies. That was one reason why the book Just Kids was attractive to me. The other reason I was attracted to the book was because it won the 2010 National Book Award for non-fiction.

But more than just learning about the punk era and the people who took the revolution of the 1960s and moved it into the 1970s and 80s, this is a book about the spirit that moves people to become the artists, musicians, actors, and writers of any decade. For that reason, it is a book about the universality of creativity.

Patti Smith left her home in New Jersey in the mid 1960s and moved to New York. Almost immediately she met a young man, just her age, who had also arrived in the city from Long Island. His name was Robert Mapplethorpe, and for the next five or six years, they were inseparable partners and co-creators of art and poetry. Each went on to become famous--Robert as photographer, Patti as singer and poet, but they remained best friends until Mapplethorpe’s death from AIDS in 1989.

They lived for a while at the Chelsea Hotel, where anyone who was anyone stayed; they ate at the restaurant where Andy Warhol ate. She mentions one meal at a restaurant where Jimi Hendrix and Janis Joplin were both eating. She talks about the time that Allen Ginsburg tried to pick her up, thinking she was a cute young boy. Yet, this is not primarily a name-dropping book. Most of the names dropped are people who helped them, people who supported them, and people who encouraged them. Patti and Robert knew how to find the people who could help them the most. And because they were so uniquely gifted, both of them were able to find the audiences that would appreciate their work. One reviewer suggested that a cultural historian will love the cornucopia of people so succinctly evaluated. He also mentions, “Just Kids is the most spellbinding and diverting portrait of funky-but-chic New York in the late ’60s and early ’70s that any alumnus has committed to print.”

This is a very lyrical book; Patti Smith is a poet, and nearly every paragraph has phrases that are beautifully crafted and heart-breakingly beautiful. A beautiful passage:

“Where does it all lead? What will become of us? These were our young questions, and young answers were revealed. It leads to each other. We became ourselves. For a time, Robert protected me, then was dependent on me, and then possessive of me. His transformation was the rose of Genet, and he was pierced deeply by his blooming. I too desired to feel more of the world. Yet sometimes that desire was nothing more than a wish to go backward where our mute light spread from hanging lanterns with mirrored panels. We had ventured out like Maeterlinck’s children seeking the bluebird and were caught in the twisted briars of our new experiences.”

One of the most touching moments comes when Robert takes Patti’s photo for her album, Horses. She says about the portrait: “When I look at it now, I never see me, I see us.” I cried as I read the last chapters about Patti’s new life as a singer, a wife and a mother and when I read of Robert’s illness and death. What had been their young lives had been transformed into something quite different, but the reader must cry for what had been, and for the bond that sustained them.

The Washington Post reviewer has the last word:

“More than a 1970s bohemian rhapsody, Just Kids is one of the best books ever written on becoming an artist -- not the race for online celebrity and corporate sponsorship that often passes for artistic success these days, but the far more powerful, often difficult journey toward the ecstatic experience of capturing radiance of imagination on a page or stage or photographic paper."

When I mentioned this book to my sister-in-law, Arna, who is 10 years younger than me, she knew all about Robert Mapplethorpe and Patti Smith. She has lived that bohemian artist lifestyle, and she knows the process of artistic development. Just Kids is a book for all of us, whether for me, who knew nothing of the times or the author, or for people like Arna, who lived a similar experience. It is an incredible book.

New York Times Reviews:

http://www.nytimes.com/2010/01/18/books/18book.html

http://www.nytimes.com/2010/01/31/books/review/Carson-t.html

The Washington Post Review:

http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2010/01/25/AR2010012503700.html

An interview with Patti Smith on NPR’s Fresh Air:

http://www.npr.org/templates/story/story.php?storyId=122722618

Patti Smith’s Website:

http://www.pattismith.net/

New York, Harper Collins, 2010

288 pages Memoir

Up there, Down there

from Dream of Life by Patti Smith

Up there, there’s a ball of fire

Some call it the spirit, some call it the sun.

It’s energies are not for hire.

It serves man, it serves everyone.

I am listening to Patti Smith music today, trying to connect with an era I missed completely, because I was studying theology--of all things--getting married and having babies. That was one reason why the book Just Kids was attractive to me. The other reason I was attracted to the book was because it won the 2010 National Book Award for non-fiction.

But more than just learning about the punk era and the people who took the revolution of the 1960s and moved it into the 1970s and 80s, this is a book about the spirit that moves people to become the artists, musicians, actors, and writers of any decade. For that reason, it is a book about the universality of creativity.

Patti Smith left her home in New Jersey in the mid 1960s and moved to New York. Almost immediately she met a young man, just her age, who had also arrived in the city from Long Island. His name was Robert Mapplethorpe, and for the next five or six years, they were inseparable partners and co-creators of art and poetry. Each went on to become famous--Robert as photographer, Patti as singer and poet, but they remained best friends until Mapplethorpe’s death from AIDS in 1989.

They lived for a while at the Chelsea Hotel, where anyone who was anyone stayed; they ate at the restaurant where Andy Warhol ate. She mentions one meal at a restaurant where Jimi Hendrix and Janis Joplin were both eating. She talks about the time that Allen Ginsburg tried to pick her up, thinking she was a cute young boy. Yet, this is not primarily a name-dropping book. Most of the names dropped are people who helped them, people who supported them, and people who encouraged them. Patti and Robert knew how to find the people who could help them the most. And because they were so uniquely gifted, both of them were able to find the audiences that would appreciate their work. One reviewer suggested that a cultural historian will love the cornucopia of people so succinctly evaluated. He also mentions, “Just Kids is the most spellbinding and diverting portrait of funky-but-chic New York in the late ’60s and early ’70s that any alumnus has committed to print.”

This is a very lyrical book; Patti Smith is a poet, and nearly every paragraph has phrases that are beautifully crafted and heart-breakingly beautiful. A beautiful passage:

“Where does it all lead? What will become of us? These were our young questions, and young answers were revealed. It leads to each other. We became ourselves. For a time, Robert protected me, then was dependent on me, and then possessive of me. His transformation was the rose of Genet, and he was pierced deeply by his blooming. I too desired to feel more of the world. Yet sometimes that desire was nothing more than a wish to go backward where our mute light spread from hanging lanterns with mirrored panels. We had ventured out like Maeterlinck’s children seeking the bluebird and were caught in the twisted briars of our new experiences.”

One of the most touching moments comes when Robert takes Patti’s photo for her album, Horses. She says about the portrait: “When I look at it now, I never see me, I see us.” I cried as I read the last chapters about Patti’s new life as a singer, a wife and a mother and when I read of Robert’s illness and death. What had been their young lives had been transformed into something quite different, but the reader must cry for what had been, and for the bond that sustained them.

The Washington Post reviewer has the last word:

“More than a 1970s bohemian rhapsody, Just Kids is one of the best books ever written on becoming an artist -- not the race for online celebrity and corporate sponsorship that often passes for artistic success these days, but the far more powerful, often difficult journey toward the ecstatic experience of capturing radiance of imagination on a page or stage or photographic paper."

When I mentioned this book to my sister-in-law, Arna, who is 10 years younger than me, she knew all about Robert Mapplethorpe and Patti Smith. She has lived that bohemian artist lifestyle, and she knows the process of artistic development. Just Kids is a book for all of us, whether for me, who knew nothing of the times or the author, or for people like Arna, who lived a similar experience. It is an incredible book.

New York Times Reviews:

http://www.nytimes.com/2010/01/18/books/18book.html

http://www.nytimes.com/2010/01/31/books/review/Carson-t.html

The Washington Post Review:

http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2010/01/25/AR2010012503700.html

An interview with Patti Smith on NPR’s Fresh Air:

http://www.npr.org/templates/story/story.php?storyId=122722618

Patti Smith’s Website:

http://www.pattismith.net/

Labels:

1970s,

Memoirs,

Patti Smith,

Punk Music,

Robert Mapplethorpe

Saturday, January 8, 2011

Saturday

by Ian McEwan

New York, Anchor Books, 2005

289 pages Fiction

Seven years after 9/11, I was taking my 10-year-old grandson, Maxwell, into Washington for the day. We had been visiting friends in Annapolis, and this was our day in the city—a part of his 10-year-old adventure, something we have shared with all our grandchildren. He was extremely agitated as we waited for the train, and his anxiety was beginning to cut into the pleasures of the day. I asked him what was worrying him so much. He replied, “I’m afraid we’re going to die.” When I expressed incredulity, he responded, “Well, a train like this would be a perfect target for terrorists.” And the shock of 9/11 washed over me again.

A similar shock stuns the protagonist of Saturday, Henry Perowne, as he views through his window a burning plane begin its descent into Heathrow airport in the early morning hours of Saturday, Feb. 25, 2003. Of course, it must be a terrorist attack, he thinks. We follow Perowne through this Saturday, his day off. We know what happens to him and what he is thinking from the moment of the burning plane until he goes to sleep much later. This is the day of the largest war protest in British history, and that event as well as the burning plane, are the background to the activities and the tragedies of the day.

Henry Perowne is a person that I would know. He is a successful neurosurgeon, happy with his career, his marriage and his children. His thoughts, like those of most intellectuals, are filled with the nuances of life, a grand mixture of family concerns, professional concerns, political concerns, mystical ramblings, and theological pronouncements (although he would not call them so.)We are privy to these thoughts as this consequential day evolves. Ostensibly, it is going to be a day that includes intimacy with his wife, who he loves dearly, a squash game with his friend and fellow doctor, a visit to his mother in her nursing home, a quick drop-in at the rehearsal for his son’s band, and the creation of a fish stew for the return of his daughter and his father-in-law. All-in-all an ordinary Saturday. The day off is interrupted by some ominous events that cloud his thinking and disrupt the order of his day. Although the events are disturbing and shattering, they are not enough to destroy this man or this family, grounded as they are in goodness and decency.

We continue to be impressed by how Henry Perowne responds to the events of the day. We are constantly aware of the tension that exists between “the public and the personal," as one reviewer noted. He goes about the business of living, even though highly confusing and terrifying things are happening to him and around him. The world around him is in chaos. The Times reviewer notes this: “In lieu of any larger social cohesion, McEwan suggests such private joys, carved out from the clamorous world, are what must sustain us. They are our fleeting glimpses of utopia; the ancient ideals of caritas and community lived in microcosm.”

It is a tense novel because we spend the most of the book wading through Perowne’s thoughts, waiting for the other shoe (the denouement) to fall. I was touched by so many of the ordinary events of the day—the visit to the mother in the nursing home, and the announcement that the daughter was pregnant—these are both things for which I had an immediate response. I understood on a visceral level his ambivalence to the buildup to the war, and the horror of watching the burning airplane. And I could empathize with his desire to help the man who put his family at risk. He is the very decent man at the beginning of the book, and a very decent man at the end of the book.

Ian McEwen is one of Britain’s most revered authors. Saturday is the first of his books that I have read. He says it is one of his most autobiographical. It was sent to me by a friend as a way to expose me to one of her favorite authors. There are many more literate reviews of this book, along with reviews for his other acclaimed books including Atonement, and Amsterdam. I would refer you to the New York Times review, which featured him in their book review magazine of March, 2005.

http://www.nytimes.com/indexes/2005/03/20/books/authors/index.html

All I can add is that after you begin to read really good literature, you become impatient with the garbage that masquerades as literature. It has its place, of course, but there is something to be said for a book that makes you ponder your very existence as you sit quietly in the firelight after the final sentence is read.

Here is an interesting interview with McEwan about Saturday:

http://www.theage.com.au/articles/2005/01/28/1106850082840.html

New York, Anchor Books, 2005

289 pages Fiction

Seven years after 9/11, I was taking my 10-year-old grandson, Maxwell, into Washington for the day. We had been visiting friends in Annapolis, and this was our day in the city—a part of his 10-year-old adventure, something we have shared with all our grandchildren. He was extremely agitated as we waited for the train, and his anxiety was beginning to cut into the pleasures of the day. I asked him what was worrying him so much. He replied, “I’m afraid we’re going to die.” When I expressed incredulity, he responded, “Well, a train like this would be a perfect target for terrorists.” And the shock of 9/11 washed over me again.

A similar shock stuns the protagonist of Saturday, Henry Perowne, as he views through his window a burning plane begin its descent into Heathrow airport in the early morning hours of Saturday, Feb. 25, 2003. Of course, it must be a terrorist attack, he thinks. We follow Perowne through this Saturday, his day off. We know what happens to him and what he is thinking from the moment of the burning plane until he goes to sleep much later. This is the day of the largest war protest in British history, and that event as well as the burning plane, are the background to the activities and the tragedies of the day.

|

| The War Protest in London (from Life Magazine) |

Henry Perowne is a person that I would know. He is a successful neurosurgeon, happy with his career, his marriage and his children. His thoughts, like those of most intellectuals, are filled with the nuances of life, a grand mixture of family concerns, professional concerns, political concerns, mystical ramblings, and theological pronouncements (although he would not call them so.)We are privy to these thoughts as this consequential day evolves. Ostensibly, it is going to be a day that includes intimacy with his wife, who he loves dearly, a squash game with his friend and fellow doctor, a visit to his mother in her nursing home, a quick drop-in at the rehearsal for his son’s band, and the creation of a fish stew for the return of his daughter and his father-in-law. All-in-all an ordinary Saturday. The day off is interrupted by some ominous events that cloud his thinking and disrupt the order of his day. Although the events are disturbing and shattering, they are not enough to destroy this man or this family, grounded as they are in goodness and decency.

We continue to be impressed by how Henry Perowne responds to the events of the day. We are constantly aware of the tension that exists between “the public and the personal," as one reviewer noted. He goes about the business of living, even though highly confusing and terrifying things are happening to him and around him. The world around him is in chaos. The Times reviewer notes this: “In lieu of any larger social cohesion, McEwan suggests such private joys, carved out from the clamorous world, are what must sustain us. They are our fleeting glimpses of utopia; the ancient ideals of caritas and community lived in microcosm.”

It is a tense novel because we spend the most of the book wading through Perowne’s thoughts, waiting for the other shoe (the denouement) to fall. I was touched by so many of the ordinary events of the day—the visit to the mother in the nursing home, and the announcement that the daughter was pregnant—these are both things for which I had an immediate response. I understood on a visceral level his ambivalence to the buildup to the war, and the horror of watching the burning airplane. And I could empathize with his desire to help the man who put his family at risk. He is the very decent man at the beginning of the book, and a very decent man at the end of the book.

Ian McEwen is one of Britain’s most revered authors. Saturday is the first of his books that I have read. He says it is one of his most autobiographical. It was sent to me by a friend as a way to expose me to one of her favorite authors. There are many more literate reviews of this book, along with reviews for his other acclaimed books including Atonement, and Amsterdam. I would refer you to the New York Times review, which featured him in their book review magazine of March, 2005.

http://www.nytimes.com/indexes/2005/03/20/books/authors/index.html

All I can add is that after you begin to read really good literature, you become impatient with the garbage that masquerades as literature. It has its place, of course, but there is something to be said for a book that makes you ponder your very existence as you sit quietly in the firelight after the final sentence is read.

Here is an interesting interview with McEwan about Saturday:

http://www.theage.com.au/articles/2005/01/28/1106850082840.html

Monday, January 3, 2011

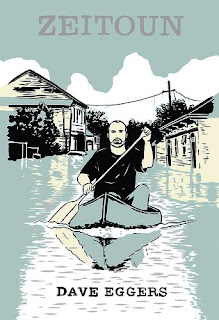

Zeitoun

By Dave Eggers

New York, Vintage Books, 2009

Non-Fiction 325 pages

Abdulrahman Zeitoun (pronounced Zaytoon) is a Syrian-American contractor and property owner in New Orleans LA. The son of a prosperous seafaring family in Syria, he immigrated to the United States as a young man, married Kathy, a Muslim convert, and settled down to run a business and raise a family in New Orleans. He is by any measure a successful businessman, well-respected in the community.

Zeitoun by Dave Eggers is the story of Hurricane Katrina as the disaster was experienced by Abdulrahman, Kathy and their four children. When Abdulrahman decided to remain in the city to guard their house and other properties, they knew that leaving was the best thing for their children, and Kathy left with much fear and trepidation. Eggers uses a day-by-day format to tell the story; first what is happening to Abdul and then what is happening to Kathy and the children--Zeitoun in the midst of the flood; Kathy in Baton Rouge and then in Phoenix, refugees from the storm.

Zeitoun is a gentle man; Kathy a take-charge sort of woman. They form a great partnership when they are together, but both suffer terribly when they are separated by the unfolding tragedy. You can’t help but like Zeitoun. The first thing he does when the water reaches the second floor of his house is to free the fish from the fish tank, so they will have a chance of survival. He sleeps on the roof of the house in a tent, but he curls up on his daughter’s bed, missing his children terribly. Daily he travels the city in a used canoe, feeding dogs, checking on friend’s property, finding help for neighbors in need. He is a very good man. So, when he is arrested as a terrorist and thrown into a makeshift jail at the Greyhound station, the injustice of it all cuts through the reader like a knife. How dare they!

This is a masterfully written book. Zeitoun reads like a novel, building slowly at first developing the characters and the setting and then when the unbelievable happens, the reader is so embroiled in the plot that you are transfixed and can’t stop reading. Eggers has a journalist’s eye for detail and some of the book reads like a newspaper account, as well. The reviewer for the New Orleans Times-Picayune says, “One of the great achievements of this book is its description of the drowned city, seen through Zeitoun's observant eyes. Eggers brings to life the eerie quiet, the sloshing of waves in places where waves are not supposed to be, the faint cries for help, the sound of dogs barking.”

For that reason, I had trouble deciding if this were a biography or a general non-fiction book. The story of Abdul and Kathy Zeitoun is more than a biography; it is the tale of an entire city, a failed government, of immigration, and terrorism, and human frailty as well as courage. It is a story of “suspense blended with just enough information to stoke reader outrage and what is likely to be a typical response: How could this happen in America?” (NY Times reviewer)

The epilogue tells of the Zeitoun’s life in the years following the storm. They were interviewed for McSweeney’s “Voices of the Storm” where Dave Eggers, the founder of McSweeney’s publishing company, heard their story and realized there was a book in there. Together, with the Zeitoun family, the story emerged. Eggers and the Zeitoun family have also begun a foundation, The Zeitoun Foundation, to support the redevelopment of New Orleans but also to speak about human rights and incarceration.

The reviewer for the New Orleans Times Picayune sums up her review with this words: “so fierce in its fury, so beautiful in its richly nuanced, compassionate telling of an American tragedy, and finally, so sweetly, stubbornly hopeful.” I can only concur.

The entire review in the Times Picayune:

http://www.nola.com/books/index.ssf/2009/07/abdulrahman_zeitouns_poetkatri.html

The review in the New York Times:

http://www.nytimes.com/2009/08/16/books/review/Egan-t.html

An interview with Abdul and Kathy Zeitoun on the Tavis Smiley show:

http://www.pbs.org/wnet/tavissmiley/archive/201008/20100827_adbulrahmanandkath.html#video

Website for McSweeney’s:

http://www.mcsweeneys.net/

New York, Vintage Books, 2009

Non-Fiction 325 pages

Abdulrahman Zeitoun (pronounced Zaytoon) is a Syrian-American contractor and property owner in New Orleans LA. The son of a prosperous seafaring family in Syria, he immigrated to the United States as a young man, married Kathy, a Muslim convert, and settled down to run a business and raise a family in New Orleans. He is by any measure a successful businessman, well-respected in the community.

Zeitoun by Dave Eggers is the story of Hurricane Katrina as the disaster was experienced by Abdulrahman, Kathy and their four children. When Abdulrahman decided to remain in the city to guard their house and other properties, they knew that leaving was the best thing for their children, and Kathy left with much fear and trepidation. Eggers uses a day-by-day format to tell the story; first what is happening to Abdul and then what is happening to Kathy and the children--Zeitoun in the midst of the flood; Kathy in Baton Rouge and then in Phoenix, refugees from the storm.

Zeitoun is a gentle man; Kathy a take-charge sort of woman. They form a great partnership when they are together, but both suffer terribly when they are separated by the unfolding tragedy. You can’t help but like Zeitoun. The first thing he does when the water reaches the second floor of his house is to free the fish from the fish tank, so they will have a chance of survival. He sleeps on the roof of the house in a tent, but he curls up on his daughter’s bed, missing his children terribly. Daily he travels the city in a used canoe, feeding dogs, checking on friend’s property, finding help for neighbors in need. He is a very good man. So, when he is arrested as a terrorist and thrown into a makeshift jail at the Greyhound station, the injustice of it all cuts through the reader like a knife. How dare they!

This is a masterfully written book. Zeitoun reads like a novel, building slowly at first developing the characters and the setting and then when the unbelievable happens, the reader is so embroiled in the plot that you are transfixed and can’t stop reading. Eggers has a journalist’s eye for detail and some of the book reads like a newspaper account, as well. The reviewer for the New Orleans Times-Picayune says, “One of the great achievements of this book is its description of the drowned city, seen through Zeitoun's observant eyes. Eggers brings to life the eerie quiet, the sloshing of waves in places where waves are not supposed to be, the faint cries for help, the sound of dogs barking.”

For that reason, I had trouble deciding if this were a biography or a general non-fiction book. The story of Abdul and Kathy Zeitoun is more than a biography; it is the tale of an entire city, a failed government, of immigration, and terrorism, and human frailty as well as courage. It is a story of “suspense blended with just enough information to stoke reader outrage and what is likely to be a typical response: How could this happen in America?” (NY Times reviewer)

The epilogue tells of the Zeitoun’s life in the years following the storm. They were interviewed for McSweeney’s “Voices of the Storm” where Dave Eggers, the founder of McSweeney’s publishing company, heard their story and realized there was a book in there. Together, with the Zeitoun family, the story emerged. Eggers and the Zeitoun family have also begun a foundation, The Zeitoun Foundation, to support the redevelopment of New Orleans but also to speak about human rights and incarceration.

The reviewer for the New Orleans Times Picayune sums up her review with this words: “so fierce in its fury, so beautiful in its richly nuanced, compassionate telling of an American tragedy, and finally, so sweetly, stubbornly hopeful.” I can only concur.

The entire review in the Times Picayune:

http://www.nola.com/books/index.ssf/2009/07/abdulrahman_zeitouns_poetkatri.html

The review in the New York Times:

http://www.nytimes.com/2009/08/16/books/review/Egan-t.html

An interview with Abdul and Kathy Zeitoun on the Tavis Smiley show:

http://www.pbs.org/wnet/tavissmiley/archive/201008/20100827_adbulrahmanandkath.html#video

Website for McSweeney’s:

http://www.mcsweeneys.net/

Labels:

Hurricane Katrina,

New Orleans,

Non-Fiction

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)