by Annia Ciezadlo

New York, Free Press, 2011

382 pages Memoir

For about twenty years, I taught elementary school with Chafic Khalid, an immigrant from Lebanon. Not only was Chafic one of the best teachers I have ever known, he was also a great cook. He had turned the small office in his classroom into a kitchen, where he prepared his midday meal when the children were out on the playground. Smells of rice and kabob would emanate down the hallway; frequently, he would fill the staff lounge with baklava and Lebanese cookies. Once a week, his students would cook and share political discussions—they were fourth graders and students of the world. My son, who was his student, loved him. Chafic died way too young; the school community still speaks of him with love.

I thought of Chafic on Wednesday, when my daughters and I prepared supper from the recipes at the back of the book Day of Honey by Annia Ciezadlo. We cooked Kafta (p. 334), which we grilled, Yakjnet Sbanegh (p. 354), tabouleh, raita, hummus and pita, pilaf, and rice pudding. It was a feast. We laughed and cooked and chatted, and then rated our meal. We all liked the Yakjnet Sbanegh the best. The taglieh, a cilantro-garlic paste (p. 341) was so aromatic that the whole house smelled like a Lebanese restaurant. The kafta was also very good. We had a wonderful time.

Day of Honey is not a cookbook, although it has recipes. It is the memoir by an American journalist who joins her Lebanese husband, Mohamad Bazzi, in covering the Iraq war for their respective newspapers. They stop first to spend their honeymoon with Mohamad’s family in Beirut. They then move on to Baghdad where they live in a hotel and cover the war until it becomes too dangerous. They move back to Beirut hoping that things will be more peaceful, but increasing violence there makes life difficult for them as well. For six years, they live at the edge of war and try to carry on normal lives, all the time flirting with death and destruction.

The New York Times reviewer says of the memoir: “It’s a carefully researched tour through the history of Middle Eastern food. It’s filled with adrenalized scenes from war zones, scenes of narrow escapes and clandestine phone calls and frightening cultural misunderstandings.” Food is what ties the whole story together. Ciezadlo recounts what they were eating when they talked to sheikhs and members of the Iraqi parliament. She remembers the streets of Beirut, not by the street name, but by the name of the restaurant that sits on the corner. She seeks out recipes from hosts at dinner parties and farmers at the market.

The more difficult life becomes for them, the more obsessive Ciezadlo becomes about cooking and about food. But living in hotels makes cooking very difficult. She says; “I wanted dinner with friends, and not in a restaurant. I wanted to invite friends over and serve them food—my food, made with my hands.”

In the end, Ciezadlo and her husband returned to the United States where they live in New York City. When she misses Beirut and Baghdad, she cooks a meal and invites people to sit around the table and converse. “Breaking bread was the oldest and best excuse for such an occasion. It was how you created your own tribe, a microcosm of the world you want to live in.”

The New York Times reviewer sums it up: “Her book is among the least political, and most intimate and valuable, to have come out of the Iraq war.” As she says in closing: “Food alone cannot make peace. It is part of war, like everything else. We can break bread with our neighbors one day and kill them the next. Food is just an excuse—an opportunity to get to know your neighbors. When you share it with others, it becomes something more.”

Chafic knew that as he spread good will throughout our school with his baklava and falafel; we knew that last night as we cooked the recipes we had never tried before and served our husbands our creations, using the pita to clean up the very last of the garlic sauce from the spinach stew. Annia Ciezadlo knew that as she bargained with the lady selling green garlic in the Beirut market. Food heals.

Don’t be put off by the nonsensical book jacket with its pretty little girl sitting among the roses; this book is much more significant than the jacket implies. Day of Honey came to me from the publisher, and there are many bloggers publishing their reviews today. I am anxious to see what others thought.

The review in the New York Times: http://www.nytimes.com/2011/02/07/books/07book.html

Annia Ciezadlo’s website: http://www.anniaciezadlo.com/

Here is an interview with Annia Ciezadlo: http://www.carahoffman.com/blog.htm?post=770894

Welcome to my blog. I am Miriam Downey, the Cyberlibrarian. I am a retired librarian and a lifelong reader. I read and review books in four major genres: fiction, non-fiction, memoir and spiritual. My goal is to relate what I read to my life experience. I read books culled from reviews in The New York Times, The New York Review of Books, Bookmarks, and The New Yorker. I also accept books from authors and publicists. I am having a great time. Hope you will join me on the journey.

Search

Thursday, February 24, 2011

Thursday, February 17, 2011

One Thousand Gifts: A Dare to Live Fully Right Where You Are

By Ann Voskamp

Grand Rapids MI, Zondervan, 2010

237 p. Spiritual

Last week when it was 5° above zero, the sun rose as we were eating breakfast. My husband exclaimed about the beauty of the sunlight on the hard crystals of snow; I complained that I wished we were out of here and in Florida or someplace warm. It was in that atmosphere that I picked up One Thousand Gifts, a book that I had just purchased for the church library. It was good that I picked it up, because by afternoon I was out walking in the sunny snow.

Ann Voskamp is a Canadian farm wife in southwestern Ontario. I can envision where she lives because we drive through that area on our way to Stratford Ontario and the Shakespeare Festival. She has six children that she home schools, she runs a blog called “A Holy Experience” and has written this small inspirational book, which itself has spawned a website. The theme of the book is finding thanksgiving or eucharisteo in the everyday.

I was reminded of the book I read in May last year, The Happiness Project by Gretchen Rubin. However, there are two distinctions; Rubin’s book is secular, Voskamp’s is religious, and Rubin’s plan for happiness comes from a need to organize anxiety, Voskamp’s from a need to quell anxiety. Both women were concerned that the mundane necessities of family life were dragging down their feelings of joy and self-worth, and both found security and peace in looking for the good in their lives. I was reminded frequently of the old saying, “If Mom ain’t happy, ain’t nobody happy.”

The questions I faced as I read One Thousand Gifts was: “What can a 60-something woman gain from reading an inspirational book written by a much younger mother of small children?” “How can a religious skeptic grow from reading a book by a more traditional Christian?”

Voskamp writes in a sing-song poetic style that is more fragmented than cohesive, more impressionistic than linear. Sometimes, I felt that she got caught up in the flow and beauty of her words. “Get to the point, already!” Sometimes, but not often, I felt her thanksgivings were simplistic. Mostly, however, I gloried with her in her thanksgivings, her eucharisteos. What I especially appreciate about her writing is that she backs up her own thoughts with the writings of the great thinkers, theologians, and writers. She inserts quotes from C. S. Lewis, G. K. Chesterton, Teresa of Avila, and Henri Nouwen, among others. Bible verses and stories form the basis of most of her ponderings. She rises above platitude, which would have been easy in this type of inspirational book, primarily because she doesn’t follow the simple “praise God” path. She acknowledges weakness, failure, and fear; she acknowledges that sometimes grace is hard to find; yet, she continues to cook her meals, teach her children, and wash her dishes, celebrating the sunlit rainbow in the soap bubble.

Even I, 30 years her senior, could understand and appreciate her prayers and her thanksgivings. I particularly liked this statement. “Endless thanksgiving, eucharisteo, has opened me to this, the way of the fullest life. From initial union to intimate communion—it isn’t exclusively the domain of the monastics and ascetics, pastors and missionaries, but I, domestic scrubber of potatoes, sister to Brother Lawrence, could I have unbroken communion, fullest life with fullest God?”

There are probably many ways to find purpose in living, joy in the mundane and the sacred among the secular. Ann Voskamp has discovered that among the huge challenges of living, finding joy in the very small gives life purpose, clarity and eucharisteo. I can celebrate that for her and with her.

I had trouble finding a review of this book in a regular reviewing tool, such as a newspaper, but there are many reviews in the blogosphere. Here is one of them: http://blogcritics.org/books/article/book-review-one-thousand-gifts-a/

Here is Ann Voskamp’s website: http://http://www.aholyexperience.com/

Here is the One Thousand Gifts website begun by Ann Voskamp and Zondervan, the publisher:

http://onethousandgifts.com/

Here is a recent article of Voskamp’s in the Huffington Post. It pretty much summarizes her book:

http://www.huffingtonpost.com/ann-voskamp/post_1710_b_821452.html

Grand Rapids MI, Zondervan, 2010

237 p. Spiritual

Last week when it was 5° above zero, the sun rose as we were eating breakfast. My husband exclaimed about the beauty of the sunlight on the hard crystals of snow; I complained that I wished we were out of here and in Florida or someplace warm. It was in that atmosphere that I picked up One Thousand Gifts, a book that I had just purchased for the church library. It was good that I picked it up, because by afternoon I was out walking in the sunny snow.

Ann Voskamp is a Canadian farm wife in southwestern Ontario. I can envision where she lives because we drive through that area on our way to Stratford Ontario and the Shakespeare Festival. She has six children that she home schools, she runs a blog called “A Holy Experience” and has written this small inspirational book, which itself has spawned a website. The theme of the book is finding thanksgiving or eucharisteo in the everyday.

I was reminded of the book I read in May last year, The Happiness Project by Gretchen Rubin. However, there are two distinctions; Rubin’s book is secular, Voskamp’s is religious, and Rubin’s plan for happiness comes from a need to organize anxiety, Voskamp’s from a need to quell anxiety. Both women were concerned that the mundane necessities of family life were dragging down their feelings of joy and self-worth, and both found security and peace in looking for the good in their lives. I was reminded frequently of the old saying, “If Mom ain’t happy, ain’t nobody happy.”

The questions I faced as I read One Thousand Gifts was: “What can a 60-something woman gain from reading an inspirational book written by a much younger mother of small children?” “How can a religious skeptic grow from reading a book by a more traditional Christian?”

Voskamp writes in a sing-song poetic style that is more fragmented than cohesive, more impressionistic than linear. Sometimes, I felt that she got caught up in the flow and beauty of her words. “Get to the point, already!” Sometimes, but not often, I felt her thanksgivings were simplistic. Mostly, however, I gloried with her in her thanksgivings, her eucharisteos. What I especially appreciate about her writing is that she backs up her own thoughts with the writings of the great thinkers, theologians, and writers. She inserts quotes from C. S. Lewis, G. K. Chesterton, Teresa of Avila, and Henri Nouwen, among others. Bible verses and stories form the basis of most of her ponderings. She rises above platitude, which would have been easy in this type of inspirational book, primarily because she doesn’t follow the simple “praise God” path. She acknowledges weakness, failure, and fear; she acknowledges that sometimes grace is hard to find; yet, she continues to cook her meals, teach her children, and wash her dishes, celebrating the sunlit rainbow in the soap bubble.

Even I, 30 years her senior, could understand and appreciate her prayers and her thanksgivings. I particularly liked this statement. “Endless thanksgiving, eucharisteo, has opened me to this, the way of the fullest life. From initial union to intimate communion—it isn’t exclusively the domain of the monastics and ascetics, pastors and missionaries, but I, domestic scrubber of potatoes, sister to Brother Lawrence, could I have unbroken communion, fullest life with fullest God?”

There are probably many ways to find purpose in living, joy in the mundane and the sacred among the secular. Ann Voskamp has discovered that among the huge challenges of living, finding joy in the very small gives life purpose, clarity and eucharisteo. I can celebrate that for her and with her.

I had trouble finding a review of this book in a regular reviewing tool, such as a newspaper, but there are many reviews in the blogosphere. Here is one of them: http://blogcritics.org/books/article/book-review-one-thousand-gifts-a/

Here is Ann Voskamp’s website: http://http://www.aholyexperience.com/

Here is the One Thousand Gifts website begun by Ann Voskamp and Zondervan, the publisher:

http://onethousandgifts.com/

Here is a recent article of Voskamp’s in the Huffington Post. It pretty much summarizes her book:

http://www.huffingtonpost.com/ann-voskamp/post_1710_b_821452.html

Wednesday, February 16, 2011

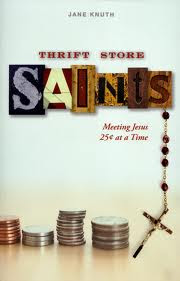

Thrift Store Saints: Meeting Jesus 25¢ at a Time

By Jane Knuth

Chicago, Loyola Press, 2010

160 p. Spiritual

Today I am preparing a talk on books about discipleship for a group of women from my church. I had included two books that I read last year, Jesus Freak by Sara Miles and Things Seen and Unseen by Nora Gallagher. I bought Thrift Store Saints by local Kalamazoo author Jane Knuth to help fill out the book talk and was also including A Monk in the Inner City by Mary Lou Kownacki, which I have yet to read. I had planned to just introduce Thrift Store Saints, so I sat down to read a bit to get the flavor of the book, and I ended reading it all in one sitting. This is a truly insightful and inspiring book.

Jane Knuth became a rather reluctant volunteer at the St. Vincent de Paul Society thrift shop in Kalamazoo more than fifteen years ago. The store operates as a regular charity thrift shop, taking in castoffs, selling or giving them away, and using the proceeds to help people with rent, heat bills, food, or other necessities. As her experience broadened, she began to realize several things: that she was changing and that her perception of the poor was changing as well. “After more than a year working at the St. Vincent de Paul shop, I still keep looking for “the deserving poor”—the innocent ones who are blatant victims of in justice and hard luck. I want to help them and no one else. From what I can see, apart from children, most poor people’s situations seem to stem from a mixture of uncontrollable circumstances, luck, and their own decisions. Same as my situation.”

In a discussion with a friend, Jane discovers the definition of what it means to be charitable. Her friend thinks that there are three kinds of charity: the “recyclable” type where you give away what you don’t want or need anymore; the “sharing” type where you give some of your resources or money to help those in need; and the third type is where you give more than you can afford for the sake of someone else. This explanation resounded with me. Sometimes giving is easy. Sometimes it is the hardest thing we do, because it is filled with our own sacrifice.

Thrift Store Saints is full of stories of the people who work at the thrift store, the people who shop at the thrift store, and the people who receive the proceeds from the store. The book is agonizingly true and poignant, while at the same time, funny and perceptive. Jane Knuth finds that the people with whom she comes in contact have as much or more to offer her as she has to offer them. Growth comes both ways.

Mary Lou Kownacki says about her soup kitchen ministry in Monk in the Inner City, “The question is not whether the soup kitchen has changed things, made a difference, brought justice to the city’s poor. The real question is have we changed? After thirty years, have we become kinder, more merciful, less judgmental? Do we continue feeding the poor because we want to see the fruits of our efforts? Or do we continue serving soup because we love? And do we love enough not to give up on anything or anyone?” Jane Knuth and her thrift store saints would add their “Amen” to that.

Review in the Kalamazoo Gazette:

Chicago, Loyola Press, 2010

160 p. Spiritual

Today I am preparing a talk on books about discipleship for a group of women from my church. I had included two books that I read last year, Jesus Freak by Sara Miles and Things Seen and Unseen by Nora Gallagher. I bought Thrift Store Saints by local Kalamazoo author Jane Knuth to help fill out the book talk and was also including A Monk in the Inner City by Mary Lou Kownacki, which I have yet to read. I had planned to just introduce Thrift Store Saints, so I sat down to read a bit to get the flavor of the book, and I ended reading it all in one sitting. This is a truly insightful and inspiring book.

Jane Knuth became a rather reluctant volunteer at the St. Vincent de Paul Society thrift shop in Kalamazoo more than fifteen years ago. The store operates as a regular charity thrift shop, taking in castoffs, selling or giving them away, and using the proceeds to help people with rent, heat bills, food, or other necessities. As her experience broadened, she began to realize several things: that she was changing and that her perception of the poor was changing as well. “After more than a year working at the St. Vincent de Paul shop, I still keep looking for “the deserving poor”—the innocent ones who are blatant victims of in justice and hard luck. I want to help them and no one else. From what I can see, apart from children, most poor people’s situations seem to stem from a mixture of uncontrollable circumstances, luck, and their own decisions. Same as my situation.”

In a discussion with a friend, Jane discovers the definition of what it means to be charitable. Her friend thinks that there are three kinds of charity: the “recyclable” type where you give away what you don’t want or need anymore; the “sharing” type where you give some of your resources or money to help those in need; and the third type is where you give more than you can afford for the sake of someone else. This explanation resounded with me. Sometimes giving is easy. Sometimes it is the hardest thing we do, because it is filled with our own sacrifice.

Thrift Store Saints is full of stories of the people who work at the thrift store, the people who shop at the thrift store, and the people who receive the proceeds from the store. The book is agonizingly true and poignant, while at the same time, funny and perceptive. Jane Knuth finds that the people with whom she comes in contact have as much or more to offer her as she has to offer them. Growth comes both ways.

Mary Lou Kownacki says about her soup kitchen ministry in Monk in the Inner City, “The question is not whether the soup kitchen has changed things, made a difference, brought justice to the city’s poor. The real question is have we changed? After thirty years, have we become kinder, more merciful, less judgmental? Do we continue feeding the poor because we want to see the fruits of our efforts? Or do we continue serving soup because we love? And do we love enough not to give up on anything or anyone?” Jane Knuth and her thrift store saints would add their “Amen” to that.

Review in the Kalamazoo Gazette:

Jane Knuth's blog: http://thriftstoresaints.com/

Friday, February 11, 2011

Strength in What Remains

by Tracy Kidder

New York, Random House, 2009

284 pages, Biography

The story of Deogratias Niyizonkiza is not an easy one to tell, nor is it easy to read. A refugee from the genocide in the tiny countries of Burundi and Rwanda, Deo, who was a medical student in Burundi, came to the United States in 1994 with nowhere to go and $200 in his pocket.

In Strength in What Remains, Tracy Kidder has chosen to tell Deo’s story in a non-linear manner, which is a bit disconcerting at first, but understandable given the subject. By beginning the story with a bit of hope—Deo’s arrival in New York—we are better prepared to read of the horrendous escape from death and destruction that he experienced.

Basically, the story is told in sections, the story of hope and lucky breaks in the United States, and the story of destruction and death in Burundi. Along the way, we learn of his childhood and education, and the goodness of people who helped him. But what can’t be denied is the horror Deo experienced as a young medical student that shapes every moment of the rest of his life.

Kidder inserts himself in the last section of the book when he goes with Deo to Burundi and Rwanda to visit Deo’s family and relive with him the experiences of the genocide. He also brings us up to date on Deo’s life, including a visit to the clinic Deo has built in Kigatu, Burundi.

Frankly, the section about the war and Deo’s escape from it is harrowing and gruesome to read. At the same time, the reader becomes engrossed in the graphic drama to such an extent that you realize that you are holding your breath. There are dead bodies everywhere, and you have to remind yourself that this is real and not some overwhelming action scene in a movie. It is absolutely heartrending. The New York Times reviewer comments, “Kidder’s rendering of what Deo endured and survived just before he boarded that plane for New York is one of the most powerful passages of modern nonfiction.”

I could not get over the overriding fact of this genocide: the Hutus and Tutsis are so closely related that most people don’t know whether their neighbors are Hutus or Tutsis…there is no distinguishing physical feature, no distinctive surname, no sign on the door. For much of his childhood, Deo didn’t even know that he was a Tutsi. The differences were primarily a construct left over from the colonial period. Additionally, when we found Rwanda and Burundi on a map, we were amazed to find that they are tiny specks among the much larger sub Saharan countries. How was it possible that hundreds of thousands of people could have died there?

The New York Times reviewer is most complimentary of Tracy Kidder’s writing in this book. He says that Kidder writes “books illuminated by a glowing humanism,” and that he is “trusting the reader enough to present characters in the full splatter of unsettling complexity. This is not about presenting a holy man, a hero. His protagonist is bold, insecure, foolish, inspiring and, as the young man’s memories race to catch him, there are hints that even more shades of personality will soon be revealed.”

Strength in What Remains is the Reading Together book for the Kalamazoo community this year. Tracy Kidder will be speaking at Chenery Auditorium on March 10. It is also the book my book club is reading for this month. My husband and I read this book aloud to each other, something we have done every day of our ten-year marriage.

Here is the New York Times review: http://www.nytimes.com/2009/08/30/books/review/Suskind-t.html

Deogratias Niyizonkiza was a 2010 Voices of Courage winner from the Women’s Refuge Commission: http://womensrefugeecommission.org/blog/969-deogratias-niyizonkiza-providing-hope-through-health-care

His organization is called Village Health Works: http://villagehealthworks.org/

Tracy Kidder’s website: http://www.tracykidder.com

Kalamazoo Public Library Reading Together: www.kpl.gov/reading-together/next.aspx

New York, Random House, 2009

284 pages, Biography

The story of Deogratias Niyizonkiza is not an easy one to tell, nor is it easy to read. A refugee from the genocide in the tiny countries of Burundi and Rwanda, Deo, who was a medical student in Burundi, came to the United States in 1994 with nowhere to go and $200 in his pocket.

In Strength in What Remains, Tracy Kidder has chosen to tell Deo’s story in a non-linear manner, which is a bit disconcerting at first, but understandable given the subject. By beginning the story with a bit of hope—Deo’s arrival in New York—we are better prepared to read of the horrendous escape from death and destruction that he experienced.

Basically, the story is told in sections, the story of hope and lucky breaks in the United States, and the story of destruction and death in Burundi. Along the way, we learn of his childhood and education, and the goodness of people who helped him. But what can’t be denied is the horror Deo experienced as a young medical student that shapes every moment of the rest of his life.

Kidder inserts himself in the last section of the book when he goes with Deo to Burundi and Rwanda to visit Deo’s family and relive with him the experiences of the genocide. He also brings us up to date on Deo’s life, including a visit to the clinic Deo has built in Kigatu, Burundi.

Frankly, the section about the war and Deo’s escape from it is harrowing and gruesome to read. At the same time, the reader becomes engrossed in the graphic drama to such an extent that you realize that you are holding your breath. There are dead bodies everywhere, and you have to remind yourself that this is real and not some overwhelming action scene in a movie. It is absolutely heartrending. The New York Times reviewer comments, “Kidder’s rendering of what Deo endured and survived just before he boarded that plane for New York is one of the most powerful passages of modern nonfiction.”

I could not get over the overriding fact of this genocide: the Hutus and Tutsis are so closely related that most people don’t know whether their neighbors are Hutus or Tutsis…there is no distinguishing physical feature, no distinctive surname, no sign on the door. For much of his childhood, Deo didn’t even know that he was a Tutsi. The differences were primarily a construct left over from the colonial period. Additionally, when we found Rwanda and Burundi on a map, we were amazed to find that they are tiny specks among the much larger sub Saharan countries. How was it possible that hundreds of thousands of people could have died there?

The New York Times reviewer is most complimentary of Tracy Kidder’s writing in this book. He says that Kidder writes “books illuminated by a glowing humanism,” and that he is “trusting the reader enough to present characters in the full splatter of unsettling complexity. This is not about presenting a holy man, a hero. His protagonist is bold, insecure, foolish, inspiring and, as the young man’s memories race to catch him, there are hints that even more shades of personality will soon be revealed.”

Strength in What Remains is the Reading Together book for the Kalamazoo community this year. Tracy Kidder will be speaking at Chenery Auditorium on March 10. It is also the book my book club is reading for this month. My husband and I read this book aloud to each other, something we have done every day of our ten-year marriage.

Here is the New York Times review: http://www.nytimes.com/2009/08/30/books/review/Suskind-t.html

Deogratias Niyizonkiza was a 2010 Voices of Courage winner from the Women’s Refuge Commission: http://womensrefugeecommission.org/blog/969-deogratias-niyizonkiza-providing-hope-through-health-care

His organization is called Village Health Works: http://villagehealthworks.org/

Tracy Kidder’s website: http://www.tracykidder.com

Kalamazoo Public Library Reading Together: www.kpl.gov/reading-together/next.aspx

Saturday, February 5, 2011

Woodsburner: A Novel

by John Pipkin

Anchor Books, 2010

366 pages Fiction

Henry David Thoreau—junior year of high school—American literature. Was this when you were introduced to Thoreau and Walden? For me, and I would guess for many, the message of Henry David Thoreau remains ingrained. I had thought before I read Woodsburner: A Novel by John Pipkin I would read Walden again, some 50 years after I had read it the first time for the demanding Mr. Burroughs. I was traveling, so I checked it out of the library in MP3 format, stuck the plugs in my ears, and proceeded to listen as I drove through a snow storm. Unfortunately, philosophy, snow, and trucks on I-94 don’t mix, so I abandoned the effort and went straight for the novel.

Woodsburner looks at an incident from the life of Henry David Thoreau—the accidental fire he started that nearly burned down the village of Concord, MA in 1844—from the perspective of the young Thoreau as well as five other people whose lives were engulfed in the fire and changed by it. Henry David Thoreau is but one of the players in the ensuing drama. The others are a Norwegian farmer, a bookseller from Boston, a fire-and brimstone preacher, and a lesbian couple recently arrived from Bohemia. Each has already been involved with fire: the farmer survived a tragic explosion; the bookseller is writing a play in which a house burns down as its climax; the preacher is expecting the earth to end in eternal flame; and the lesbian couple have escaped from being burned as witches in their native land.

Henry David Thoreau is almost a minor character in the drama, even as he is the one who began the whole thing. One reviewer says, “…he speaks and thinks in a mixture of innocence, self-righteousness, apprehension and nobility.” Although Pipkin uses Thoreau’s writing as the basis for the young man’s thoughts, he doesn’t quote it, for which I was grateful. For instance, thinking of the bookseller, the character Thoreau ponders, “You are mired in a life of desperation”… “and do not even know enough to remain quiet about it.” The author says, “It would be easy to take readers’ expectations and reinforce them. I tried to show the foundation of the man he would become while avoiding the temptation to just put some of his most quotable thoughts in his head.”

Of course Pipkin had in mind Throeau’s famous quote, “The mass of men lead lives of quiet desperation," as he began his novel, because each of these characters is in despair. With Pipkin’s skillful writing, they come to life and each finds his way out of desperation.

As I was reading this book, I was constantly thinking about Pipkin and the creative journey he was on as he wrote this book. How did he find this topic and these characters? He says, “My concern, wasn’t so much about the process of how to do it or what people would think about me doing this but about me being able to remain true to the mission of fiction—to make up a good story.” And it is a very good story. One of the things I liked the most was that the author is not bogged down in the details of the era, although there is enough detail that the setting is interesting. I am generally not a fan of historical fiction when I feel like the author is flaunting his knowledge of the time and place. Pipkin’s setting is authentic but not overwhelmingly so. In other words, this book is character driven rather than historically driven.

In closing, I have to say that I am grateful for the nudge from the author’s agent to read this book, because I would not have found it otherwise. Although it has won several awards, it has not made its way to my usual book review sources. It stretched my thinking, and for that I am grateful. I woke up this morning thinking about how I want to move my own life forward, out of the despair of the ordinary, to the adventure of the unknown.

Here is a good summary of the book: http://www.redroom.com/publishedwork/woodsburner

The review in the Washington Post:

http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2009/04/21/AR2009042103511.html

An interview on an Austin TX radio station: http://kut.org/items/show/16643

John Pipkin’s website: http://web.mac.com/pipkinjohn/iWeb/Site/About%20the%20Author.html

Anchor Books, 2010

366 pages Fiction

Henry David Thoreau—junior year of high school—American literature. Was this when you were introduced to Thoreau and Walden? For me, and I would guess for many, the message of Henry David Thoreau remains ingrained. I had thought before I read Woodsburner: A Novel by John Pipkin I would read Walden again, some 50 years after I had read it the first time for the demanding Mr. Burroughs. I was traveling, so I checked it out of the library in MP3 format, stuck the plugs in my ears, and proceeded to listen as I drove through a snow storm. Unfortunately, philosophy, snow, and trucks on I-94 don’t mix, so I abandoned the effort and went straight for the novel.

Woodsburner looks at an incident from the life of Henry David Thoreau—the accidental fire he started that nearly burned down the village of Concord, MA in 1844—from the perspective of the young Thoreau as well as five other people whose lives were engulfed in the fire and changed by it. Henry David Thoreau is but one of the players in the ensuing drama. The others are a Norwegian farmer, a bookseller from Boston, a fire-and brimstone preacher, and a lesbian couple recently arrived from Bohemia. Each has already been involved with fire: the farmer survived a tragic explosion; the bookseller is writing a play in which a house burns down as its climax; the preacher is expecting the earth to end in eternal flame; and the lesbian couple have escaped from being burned as witches in their native land.

Henry David Thoreau is almost a minor character in the drama, even as he is the one who began the whole thing. One reviewer says, “…he speaks and thinks in a mixture of innocence, self-righteousness, apprehension and nobility.” Although Pipkin uses Thoreau’s writing as the basis for the young man’s thoughts, he doesn’t quote it, for which I was grateful. For instance, thinking of the bookseller, the character Thoreau ponders, “You are mired in a life of desperation”… “and do not even know enough to remain quiet about it.” The author says, “It would be easy to take readers’ expectations and reinforce them. I tried to show the foundation of the man he would become while avoiding the temptation to just put some of his most quotable thoughts in his head.”

Of course Pipkin had in mind Throeau’s famous quote, “The mass of men lead lives of quiet desperation," as he began his novel, because each of these characters is in despair. With Pipkin’s skillful writing, they come to life and each finds his way out of desperation.

As I was reading this book, I was constantly thinking about Pipkin and the creative journey he was on as he wrote this book. How did he find this topic and these characters? He says, “My concern, wasn’t so much about the process of how to do it or what people would think about me doing this but about me being able to remain true to the mission of fiction—to make up a good story.” And it is a very good story. One of the things I liked the most was that the author is not bogged down in the details of the era, although there is enough detail that the setting is interesting. I am generally not a fan of historical fiction when I feel like the author is flaunting his knowledge of the time and place. Pipkin’s setting is authentic but not overwhelmingly so. In other words, this book is character driven rather than historically driven.

In closing, I have to say that I am grateful for the nudge from the author’s agent to read this book, because I would not have found it otherwise. Although it has won several awards, it has not made its way to my usual book review sources. It stretched my thinking, and for that I am grateful. I woke up this morning thinking about how I want to move my own life forward, out of the despair of the ordinary, to the adventure of the unknown.

Here is a good summary of the book: http://www.redroom.com/publishedwork/woodsburner

The review in the Washington Post:

http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2009/04/21/AR2009042103511.html

An interview on an Austin TX radio station: http://kut.org/items/show/16643

John Pipkin’s website: http://web.mac.com/pipkinjohn/iWeb/Site/About%20the%20Author.html

Labels:

Concord MA,

Henry David Thoreau,

Historical Fiction

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)